Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

One pain disorder that has uniquely captured the fascination of and induced extreme frustration in many young medical doctors is called Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Previously called “Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy” the data around this disorder has evolved dramatically over the decades. Because of this, training around it is extremely variable. For some providers, any pain that is “worse than it should be” is considered likely CRPS, while others are dismissive of the diagnosis without some arbitrary symptom being present. I can’t count the number of conversations I’ve had with physicians who say something like, “It can’t be CRPS though because the foot wasn’t that red”.

So what is this diagnosis, and why is it so difficult to find consensus? CRPS is a syndrome that has two main features. The most important feature is that the quality or severity of the pain is out of proportion to the injury. The second feature is a change in the autonomic nervous system affecting the painful area. How much and what type of pain is difficult to study since pain is so subjective, and most of the autonomic components fluctuate and are different from person to person.

Originally this disorder was identified in patients with nervous injuries near the spinal cord. It was taught that the injury also probably involved elements of the parasympathetic nerve bundles near the spine. These rare cases were studied and the diagnosis of Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy was created. These patients had severe pain that ranged from stabbing to burning that never went away. They also had changes to the coloration of the affected arm or leg, changes to the temperature, swelling, and sweating of the limb. These rare cases were more consistent, but in all actuality much of their pain was phantom limb pain and the autonomic dysfunction was due to direct injury of the parasympathetic chain. As the diagnosis expanded to include people with other types of injury to the nerves and tissues, the pain and autonomic symptoms were much more varied. The redness would come and go. The pain would be burning at times and a deep feeling of numbness at other times. This fluctuating nature of the disorder means that doctors would often dismiss it if the symptom wasn’t present in the exam room, or overdiagnose it because of a report more consistent with something like Raynaud's phenomenon.

The other problem with the diagnosis is that there are rarely any differences between effective treatments for CRPS and those effective in most other chronic pain syndromes. Anti-inflammatory treatments, tricyclic antidepressants, certain sodium or calcium modulating epilepsy drugs, Norepinephrinergic antidepressants, and a few other treatments help both, and opiates and other prescription analgesics make them worse over time. If there is no difference in the treatments, then many doctors dismiss the diagnosis as irrelevant. Patients feel very differently. The patient’s foot turns red and starts to burn and when they talk about it with doctors, they feel dismissed.

There is new research, however, showing that there is something unique about a chronic pain syndrome when it starts to involve autonomic features. Ketamine is a drug originally used for sedation during procedures, but has recently been popularized because of its effects on certain types of severe depression. While ketamine can have an effect on peripheral nerves and autonomic nerves, its main effect is to disrupt and reorganize brain networks that are involved in a variety of mood disorders and in the central sensitization process in chronic pain syndrome. In studies on chronic muscle pain, ketamine only has a modest effect. The benefits are a little better with chronic nerve pain. However, in CRPS with a significant autonomic component, ketamine’s benefits can be remarkable. Just a few infusions and patients report that the pain is significantly reduced for weeks to months. Biologically, this benefit cannot be explained in the tissue.

It begins to make a lot of sense when considering the biology of pain. First, you must realize that all pain is heavily modulated in the brain. Signals are always going to the brain, some related to pain, some pleasure, and some neutral. The brain cannot send all of these signals to conscious awareness or we wouldn’t be able to focus on the things that matter to us. The brain blocks signals all the time, and amplifies others. This is why you aren’t aware of the feeling of your socks on your feet until I mention it and then you are too distracted by the feeling to keep reading.

This is most notable during sleep when the brain turns off most signals. The brain is hardwired to turn off chronic pain signals. Have you ever known anyone with a childhood injury, a mangled arm for example? They seem like they should be in agony, but in most cases, they don’t describe much pain. The brain is also hardwired to amplify new and sudden pain signals. When you stub your toe, the brain is supposed to send off alarm bells, amplifying the pain signal so that you protect it while it heals. In chronic pain syndromes, the brain does the opposite. Chronic pain signals are amplified, and many acute pain signals are blocked out. Most of my chronic back pain patients will wake up with bruises and have no idea where they came from.

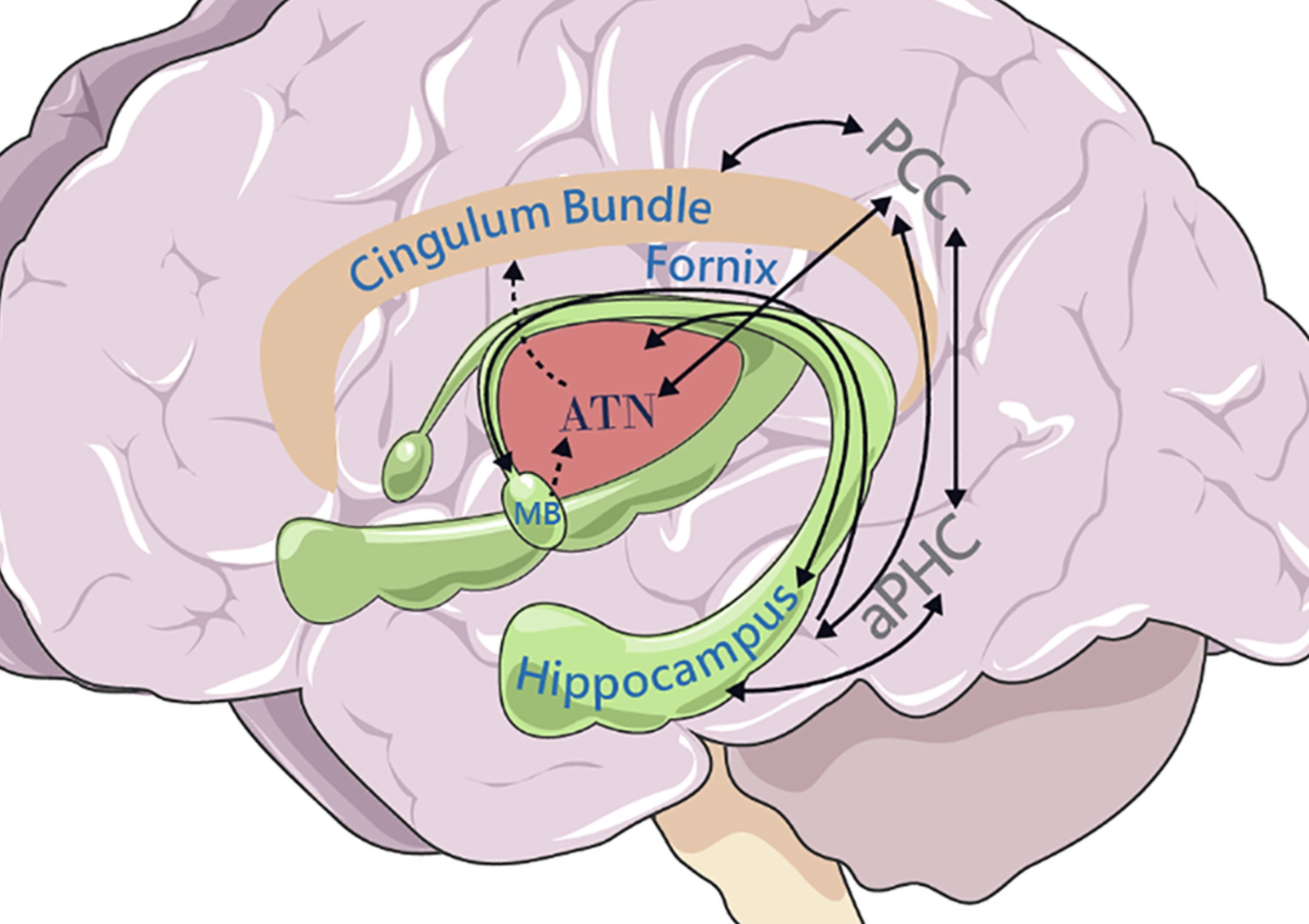

The second element of pain biology is the connection with panic and memory. It makes a lot of sense when you consider survival. If you were a person living in the wild and heard the bushes rustling, you may get a sense of panic. This panic comes from a deep unconscious memory. Last time you heard that rustling, a tiger jumped out and bit you. The pain, the memory, and the panic are all in an interconnected loop between the cingulate cortex, the thalamus, and areas in the temporal lobe. They are even stronger than regular memories and have more redundancies in the brain as proved by some very unethical studies on subjects with prior damage to the temporal lobes.

This circuit integrates memory, panic, and pain. It is mostly taught to doctors in relation to memory, but was originally discovered because it is involved in panic and psychosis. Papez Circuit.

From https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15494

The last element to understand is that the panic network in the brain has connections throughout the whole body. Before people are even aware of a feeling of panic, their heart rate changes, they begin to sweat, their bowels stop moving, and their pupils dilate. This is how lie detectors work, by measuring those autonomic responses to the subtle anxiety (often unconscious) associated with lying. There is also a jump in steroids like cortisol, and changes to other hormones like adrenaline that help regulate all of these effects. All of those hormones and autonomic nerve fibers are deeply affected in chronic pain syndrome in general, and more so in CRPS. We still have little understanding of why the autonomic nervous function in one limb are clearly more affected in most cases of CRPS, but pretending the brain isn’t in charge of the process doesn’t help. I can’t undo the physical trauma, but I can do a lot to affect the brain, the nerves, and the autonomic networks and loops in the brain and body.

Learn more by reading some of my recommended books on chronic pain, and considering my recommended gadgets, and contact us today for a consult about your pain syndrome and what tools are available to help you.